Despite what we might like to think, evidence-based interventions don’t always guarantee impact. That’s in part because a key make–or–break ingredient in this schema is all around us, but often overlooked.

What is it? Context.

And the science backs the claim.

What works in one implementation setting may not work in another. But as researchers Valéry Ridde and Claire Cole agree: that’s not failure. That’s simply the truth of the real world, that we all have to learn from.

The emerging field of Implementation Science (IS) acknowledges this reality. IS delivers frameworks to meaningfully resolve gaps that arise when we take test models out of the controlled settings in which they are born, and into the diversity of real–life environments in which we operate.

PSI chatted with Valéry Ridde, Director of Research at the French Institute for Research on Sustainable Development, and Claire Cole, PSI’s Implementation Science & Learning Advisor, to explore how IS can help teams gain important ways of thinking and doing, so that they can better set themselves up to ensure their interventions stay responsive to the people we serve, and to the unexpected complexities that are the hallmark of real-world settings.

PSI: What’s a key area where public health has missed the mark?

Valéry Ridde: Ask implementation scientists and a collective agreement reigns: health interventions are not optimal prior to implementation. Rather, it’s through implementation that we must adapt interventions so they are optimal to the contexts that surround them.

As public health practitioners, we need to move from being curious primarily about whether interventions are effective, to include curiosity about how and why they’re working, in what contexts — and for whom. How can we take into account the context surrounding the people we are working for and with, and the implementers they rely on for service? How can we improve the design of our programming, and tweak and tailor it as we implement it across varied contexts?

We often look at the impact of a health intervention without accounting for how the intervention was implemented, and what factors influenced its success or flub. As a result, when we see poor results we may deem an intervention ineffective. The intervention, however, may not be the issue. Rather, how we implemented the intervention, and how well we responded to the context that influenced our implementation, is the root we’re too often overlooking.

PSI: Why IS? Why here—why now?

Claire Cole: We achieve different impact depending on how we respond (or don’t) to the change that is part of the real world in which we implement. This is a key finding acknowledged by IS.

As implementers, we have a responsibility to recognize that a workplan and technical strategy developed at the beginning of a project will necessarily evolve in response to what arises during implementation. If we can embrace that from the outset, we can decide to set ourselves up to generate (and put to use) the types of real-time quantitative and qualitative data we need to “see” when dynamic change is happening—be it within our implementation teams, within our consumers’ communities or within the health systems our consumers depend on.

PSI: How does IS help us rethink the gaps in implementation approaches that aim to stick solely to the original intervention design?

VR: An intervention studied in a controlled environment does not account for the real-life complexities that shape whether an intervention does or doesn’t ‘work’ in real life settings. Trials provide the basis to gauge potential for effectiveness; IS offers a new way of thinking about what comes after.

Research findings support that a fidelity-only approach is rarely a sufficient process to ensure interventions can continue to deliver impact over time. IS supports implementers to make sense of what’s happening in implementation and its related results, including the rapid changes that are ongoing across all system levels in which health interventions operate (everything from standard employee turnover to regional and federal levels due to election cycles). Otherwise, we end up with interventions that are fixed rather than flexible, and ultimately cannot be sustained.

PSI: What’s an example of IS in action?

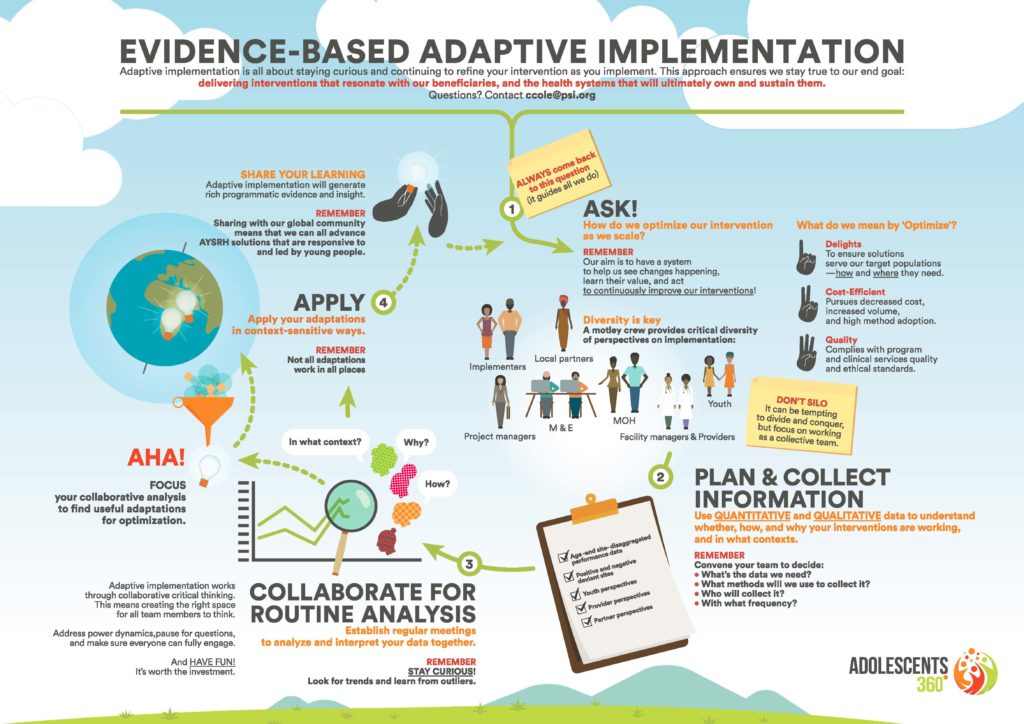

CC: We’ve applied the foundational concepts of IS to build our Adaptive Implementation approach, currently being implemented in Adolescents 360, PSI’s flagship youth-powered adolescent sexual and reproductive health program.

Click the image to see the full resolution.

It provided us with a systematic approach to understand when and how to adapt, while also helping us to make fails into a “fail fasts.”

For example, in one of our countries we wanted to reach more girls at rapid speed and scale, which meant further decentralizing mobilization responsibilities and rapidly onboarding new local partners to ‘own’ this critical component.

We, therefore, invited school teachers to engage in mobilization. But in our data monitoring, we saw the numbers of girls who turned up for A360 programming rise while voluntary contraceptive acceptance rates dipped.

We dug into our qualitative data and found that girls’ trust in the intervention was being diminished – teachers were giving girls messages to attend for reasons that were counter to the girl-powered concepts core to A360’s unique approach. For example, suggesting a girl should attend an A360 event to “learn to avoid temptation” rather than emphasizing the actual aim: to help her set plans and build skills to reach her dreams. It’s an example of how enduring adverse social norms—even when we designed to guard against them—can reemerge and disrupt in places one doesn’t expect.

Without our adaptive implementation approach, we might have continued with this same strategy for mobilization in schools and only realized when it was too late that this kind of organic adaptation was to our detriment.

PSI: How can IS help practitioners navigate when an adaptation is right—and when it can harm?

CC: Implementation scientists don’t advocate for adaptations just for the sake of adaptations. If your health intervention is a discrete medical practice— like voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) for example– then we don’t want to invite needless adaptation to how that service is delivered. But many aspects of health interventions—take for example social and behavior change communications, health system strengthening, or even the very demand generation and community engagement that needs to precede a VMMC procedure—are influenced by a multitude of complex factors. IS primes us to generate the kind of data that is necessary to think about all of these factors meaningfully, and make sense of them so that we can improve and ensure we’re delivering value for health consumers.

When we pursue an adaptive footing, we can go in knowing that we want management systems to help us pause and reflect, to understand when adaptations are beneficial versus harmful. And when they aren’t effective, we drop them. But when they do generate value—that’s critical learning and an important vote toward an intervention’s sustainability.

PSI: A360 talks about fostering a culture of curiosity through its approach. How does IS link to that, and how does it help programmers reach optimal interventions?

VR: Whether we are implementers or researchers, none of us can pretend that implementation won’t be complex. The more we can help the public health field get a sense of what it takes to work effectively in varied and changing contexts, the more precise we can get in the interventions (and policies) we are delivering. After all, global health interventions and their contexts are complex. IS enables us to learn from that as we go.

Valéry Ridde

Valéry Ridde

Director of Research at the French Institute for Research on Sustainable Development

Claire Cole

Claire Cole

PSI’s Implementation Science & Learning Advisor