Background

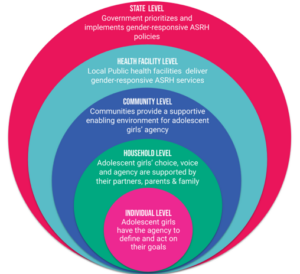

Investments in adolescents and youth (AY) as they form life-long health habits can have multiplicative effects. For many AY, norms curtail information-sharing, and leave decisions about health practices, including contraception, with family and household influencers. Shifting norms and power structures requires supportive partners and family, yet many initiatives struggle to sustain community approaches through existing systems.

To address this, two projects are testing scalable AY approaches and learning more about trade-offs required for sustainable impact.

- The Adolescents 360 (A360) project designed, implemented, adapted, and scaled interventions to support contraceptive use among adolescent girls ages 15-19 under its first phase (2016-2020). Now in its second phase (2020-2025), A360 focuses on sustainability, through technical assistance to governments in Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Kenya to scale and institutionalize interventions into government systems.

- The Connect project designed, piloted, and expanded interventions to support postpartum family planning uptake first-time mothers (ages 15-24) in Tanzania and Bangladesh. Connect’s interventions, introduced in 2021, entail light-touch “enhancements” to existing government and community health platforms.

What are we learning?

While there are many challenges related to the trade-offs of more scalable community level AY programming, both the A360 and Connect projects encountered three common challenges:

Challenge #1: Severe gaps in community health systems.

We often look to community-based health workers to scale community approaches. Yet these cadres are under-resourced and over-tasked, with heavy demands from government and projects. This limits coverage and intensity, both of which are critical for fostering shifts in norms and power structures.

Girls are often so unfamiliar and uncomfortable with available health services that they need one-on-one outreach. In Ethiopia, A360 leverages Health Extension Workers (HEWs) for tailored counseling and service delivery to married adolescent girls. However, HEWs manage a holistic health package covering 17 topics and are overburdened. A volunteer cadre – the Women’s Development Army (WDA)– can identify and mobilize girls, lowering the burden on HEWs. Yet, the extent to which the WDA is active varies by area, resulting in patchy support available to HEWs for AY outreach.

In Bangladesh, salaried, trained government Family Welfare Assistants are responsible for home visits. While they can mobilize quickly, Connect finds that they are consistently over-tasked, under-resourced, and have high vacancy rates. This results in limited coverage as they can only visit a fraction of homes. In Tanzania, volunteer CHWs require donor-funded projects to fund basic training and materials. This limits scale (because training is costly) and sustainability (since government has limited capacity to implement without external resources). Yet, project-incentivized CHWs can achieve greater dosage and intensity.

Challenge #2: Lack of platforms to engage AY household influencers.

We have found limited-to-no existing platforms that engage deeply enough with the male partners, mothers, and mothers-in-law of AY to transform norms and power structures.

In Ethiopia A360 saw that although husbands of AY want to participate in health decisions, their availability and that of HEWs is mismatched—most men are only available on weekends, when HEWs are not working. In Kenya, A360 transitioned key influencer engagement sessions over to government-led community awareness sessions. However, these existing activities do not specifically target AY influencers and provide minimal SRH information.

Similarly, by limiting engagement to existing platforms, Connect can only reach partners and mothers-in-laws through home visits and facility counseling when they are available and willing to participate. Connect’s engagement with these influencers is lighter than ideal.

To move the needle for AY, we must shift norms. Yet health systems are rarely equipped to sustain effective norms-shifting efforts at scale.

Challenge #3: Impactful approaches may not be sustainable.

Approaches that maximize impact by addressing root causes may be infeasible to implement and sustain within existing platforms—no matter how effectively they address key barriers.

In Bangladesh, Connect found that exchange visits bringing first-time mothers and their families to visit facilities to build familiarity with the health system were overwhelmingly well-received. However, visits required funding, took facility providers away from other tasks, and were outside provider job descriptions. We could not identify a path to institutionalize these visits.

A360 found that embedding soft and vocational skills made SRH interventions more attractive to girls and their influencers. However, many health systems are unable to integrate non-health activities, and expert partners are likely non-health actors. A non-health government cadre supported Connect to embed income-generating activities into community groups in Tanzania, underscoring the potential of multisectoral collaboration and the need to explore system resources beyond health. Yet coordination and follow-up often fall to donor-funded projects given the lack of mechanisms for multisectoral coordination.

Conclusions

AY are a significant portion of LMIC populations: they deserve inclusive health systems that address their needs. However, health systems have not been designed to provide what AY need. We must move away from approaches with no path to institutionalization, while supporting health systems to be more adolescent responsive.

This is much easier said than done. Implementing teams need to grapple—from the beginning—with challenging questions…

- Can government implement this approach through an existing platform without project resources?

- If an approach could potentially be fully implemented by government, what capacity needs to be built?

- If there is no path to sustainability, should we move forward? This is especially hard to answer when it comes to program elements designed to change social norms, increase agency, and shift power.

- Long-term, how can we sustainably expand health systems to accommodate what AY really need (e.g., targeted outreach, robust engagement of influencers, multi-sectoral approaches)?

None of these questions have easy answers. Yet it’s better to grapple with them early than to realize too late that an intervention has no path to sustainability. These challenges also point to the need for improved costing and consistent data sharing to better understand trade-offs.

Both projects are completing final evaluations. We will know more about the impacts in light of the trade-offs for scale. More to come!

Authors

- Mary Phillips, Technical Advisor, Adolescents 360 (A360), PSI

- Meghan Cutherell, Sr. Program Manager, Technical Services, Adolescents 360 (A360), PSI

- Melanie Yahner, Lead Advisor ASRH, Connect Project Director, Save the Children

Source : Healthy New Born Network