In Mozambique, one in two girls will marry and two in five girls will have given birth by age 18.

For the nation to achieve a demographic transition, it remains an undisputed priority to reimagine how Mozambican girls access the sexual and reproductive health (SRH) tools and services they need to own their health and life decisions. It’s a tall order – and one that PSI’s flagship Adolescents 360’s (A360) youth-powered adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health (AYSRH) programmatic blueprint is helping to drive forward.

Through UK Aid funding, Vale-a-Pena is applying the A360 approach in Mozambique: proving that by putting girls and their influencers at the center of AYSRH program design, we can better understand what it takes to position contraception as valuable, relevant and accessible for adolescent girls, today.

The project is currently in its prototyping phase.

What We Know, and What We’re Aiming to Answer

As detailed in the below table, there’s a lot about the A360 Blueprint that has been confirmed across A360’s early work in Nigeria, Tanzania and Ethiopia. It’s this framework that we wanted to validate and contextualize in Mozambique.

Girls don’t see the relevance of contraception. AYSRH services, therefore, must complement and align with girls’ self-defined and attainable joys, interests and goals—like motherhood, for when she is ready.

One size does not fit all. Segmenting programming to account for where girls are in their unique life stages enable us to better respond to girls’ differing needs.

Girls often lack safe sources—and safe spaces—to turn to for questions about their health and lives. At the same time, girls seek community acceptance yet experience a sense of social isolation as they move into new life stages, like marriage and motherhood.

Youth friendly health service provision furthers trust among consumers served, encouraging girls to return for more.

Increasing where and how girls engage with and partake in services reduces access to barriers.

Offering opt-out services removes friction by making it a norm to partake in contraceptive counseling.

Leveraging who girls define as safe influencers allows interventions to secure buy-in from those who shape how she makes her health and life decisions.

But there are new areas that present opportunities to expand what it means to take the A360 model to new places and across country contexts. Namely:

-

How can we engage influencers to understand the relevance of contraception, to thereby encourage young people to access SRH services?

-

How can we address adverse gender norms?

-

How can we engage boys so they, too, see contraception as relevant for not only their partners, but for themselves?

-

How can we engage unmarried couples, particularly in environments in which adolescents stay mum about their relationship status?

-

How should we position contraception within a context with high rates of early marriage?

Enter Vale-a-Pena

With and for young people, Vale-a-Pena aims to innovate how girls in Mozambique’s northern Nampula province and southern Gaza province aged 10-19 perceive and access modern contraception.

- The mission: From Sept. 2018 through Feb. 2019, Vale-a-Pena worked, and continues to partner with eight young designers to lay the landscape, identify the gaps and determine how the project can pave new pathways for adolescent girls to access AYSRH services.

- The context: The Vale-a-Pena team of public health, social marketing, design, social norms change partners and young designers engaged some 300 participants across Nampula (in northern Mozambique’s, with one of the country’s highest numbers of girls married [62.3%] and with child [51.7%] by age 18) and Gaza (a southern province with 40.9% of girls married, and 32.9% of girls with child before age 18). Participants ranged from girls aged 10-19 both using and not using modern contraception; and the influencers who shape their worlds: their parents; community and religious leaders; adolescent boys aged 10-19; teachers and school directors; and health providers.

- Six personas: Vale-a-Pena’s research identifies six core segments: young single mothers like “curious” Juju; young students with steady parental care in their lives like Zaida; and older girls like Susen “the younger mother” who got pregnant before marriage; Samira “the risk taker” who is a student without steady parental presence in her life and Atija “the faithful follower” who married by age 13. And of course boys: namely younger, sexually active boys with girlfriends.

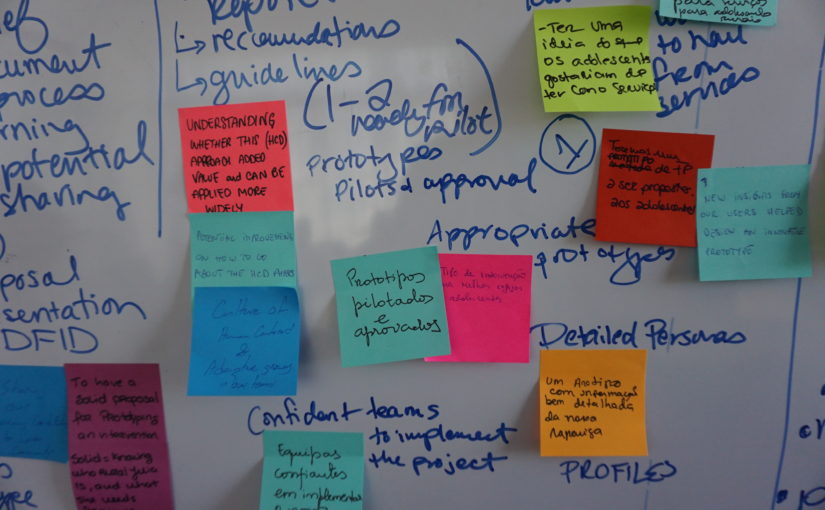

The following captures Vale-a-Pena’s findings, prototypes and flubs unveiled to date. The Mozambique team will present the findings to DFID end of February as part of the journey forward.

Setting the Scene: The Mozambican Context

Her responsibility. His decision. With child-bearing a priority among married girls, family planning is often left from consideration until a girl has had her first child. And then, it’s on her to understand her options – before sharing with her partner who weighs in on the decision.

On the down-low: Adolescents often hide their relationships given dating has yet been embraced as a community norm, posing a challenge for how young couples engage in SRH conversations.

School-based SRH education is insufficient and overlooks those who drop out of school: Mozambican adolescents predominantly glean SRH information through their secondary school education, leaving behind girls who have dropped out due to limited access, financial obstacles or distance. For girls, the SRH lessons primarily focuses on preventing pregnancy and finishing school; boys learn about the dangers of and ways to prevent contracting HIV. But with classes taught by teachers who lack deep SRH information, the team found that most adolescents cannot articulate why one should use a contraceptive method, even after undergoing the SRH curriculum.

Privacy is a priority: Girls crave confidentially when accessing SRH services, and don’t feel that health providers uphold their privacy.

Contraception remains taboo: Girls and her influencers, hold deep myths and misperceptions that contraception can harm girls’ fertility or health. Men think long-acting methods change “the taste of women” or harm her physical appearance.

Parents often push girls into early marriages to avoid the shame an unwanted pregnancy would bring onto the family. This complicates how mothers – who girls view as sources for SRH information – impart information to their daughters: namely doing so in a prohibiting way that reinforces abstinence and discourages interaction with boys.

The Low-Fidelity Prototypes Vale-a-Pena has Created, in Response

Contraceptive continuation through community-based distribution: The leading barrier to continuation of short-acting methods lies in the distance to get to a facility; community-based “kiosks” offer a viable, and trusted, solution. Women entrepreneurs, known as “promoters,” undergo training from the local health system to counsel on short-term methods – which they then do, door-to-door. But in attempt to reduce time and ease pathways to access, Vale-a-Pena is experimenting with branding promoters’ homes as kiosks for girls to get oral contraceptives and self-administered injectables. Within an environment in which public facilities are often overwhelmed by volume of clients, Vale-a-Pena is seeing providers only too happy to refer mothers and their daughters to promoters’ homes. Moreover, Vale-a-Pena trains promoters to use “Connecting with Sara,” a digital application to log and thereby track girls pathway to SRH care.

Grouping together outside of school: Vale-a-Pena’s Girl’s Group created a sense of exclusivity among girls where they could engage with peer facilitators who shared their personal reproductive health stories, while initiating “true and false” games to build bonds between girls and the group’s facilitator. Still, amendments were needed: the presence of adults, notably men, chipped at girls’ feeling of the clubs as a safe space to air burning SRH questions.

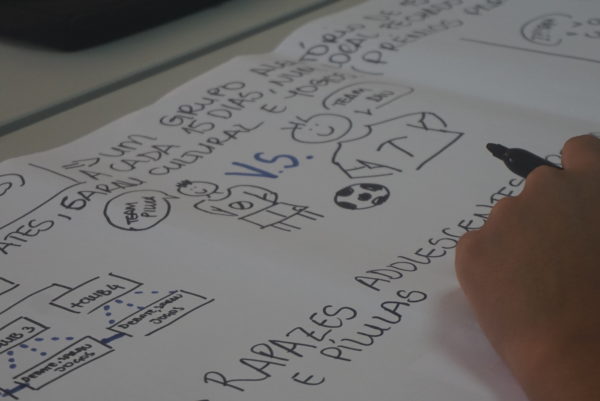

Boys, too: Boys clubs, led by male providers, tap into boys’ expressed interested in involvement in SRH conversations. Providers facilities dialogue and then distributed health facility referral coupons for boys to pass along to girls. Yet in a culture in which adolescents stay quiet about their relationships, none of the participants who took a coupon referred a girl to services.

Getting creative and confidential: Program elements like “question boxes” and “true or false games” help dispel myths and misperceptions by offering young people safe and at times anonymous ways to explore questions and concerns. Filmed testimonials played during mobile events – like the Kuwa Mjanja-inspired pop-up beauty tents and “love capsules” that offer opt-out SRH services – allows girls to see “girls like them” talking about their experience with and value in using contraception. Follow up op-out counseling removed the stigma by making it the norm for every girl to engage with a provider, unless she chooses not to.

Reaching young people where they are and how they say they need: Door-to-door distribution was identified as a model preferred by girls who fear being exposed or shamed at a health facility. In contrast, condom shops intended to reach boys with information and condoms flopped as many young people maintain deep misperceptions of condoms as a harmful method.

Mothers are key to linking girls to services: Vale-a-Pena goes where mothers are. Engaging mothers within existing community groups, like “savings” groups, where mothers are already convened provides familiar and trusted environments for mothers to dive deeper into SRH topics and receive coupons for daughters to use at health facilities. But as the initial prototype found: multiple touchpoints are necessary for mothers to support daughters in showing up for SRH services.

Addressing gender dynamics by engaging couples: Couples’ groups convened young, unmarried partners to discuss healthy relationships, their future plans and the contraceptive methods that would support them in achieving those goals. But as the team discovered, girls often go quiet with their boyfriends in the room; moreover, adolescents often keep their relationship under wraps. Reaching and mobilizing “secret” couples, therefore, poses its own challenge.

Conversation starter kits: Family Planning kits for distribution to mothers/boyfriends/partners contained all the essentials to spark all the hard SRH conversations: brochures and condoms with SRH messaging and notebooks, flowers and bracelets to appeal to girls. But the prototype’s evolution will need to tailor the kits per audience to ensure included materials speaks directly to what resonates with mothers and boys, inspiring them to want to raise SRH topics with their daughters/wives/girlfriends.

This is a learning journey

In a country with one of the highest teen pregnancy rates, the impetus remains to resolve the gaps in serving Mozambique’s next generation. That’s where Vale-a-Pena comes into play.

With and for young people, Vale-a-Pena is proving the power in adapting a youth-powered approach to determine what it takes to enact effective, resonant and ultimately lasting AYSRH behavior change in Mozambique – and beyond. Together, we can drive toward a future in which girls and young women have access to choosing the tools they need to own the lives they want.